Map: Regrid.com

Back of the Yards Workers Cottages Surveyed

In spring 2023, the Chicago Workers Cottage Initiative conducted a field survey of buildings in the Back of the Yards neighborhood in partnership with Preservation Chicago and students from UIC's Great Cities Institute. The survey was similar to previous studies of Logan Square, South Chicago and McKinley Park. Surveyors walked each street in pairs, recording information about each property via smartphone using the Regrid parcel-mapping app by Loveland Technologies. The survey aimed to cover the the northern half of the Back of the Yards neighborhood north of 47th Street, containing 31 blocks.

Photos: Tom Vlodek

Unfortunately, due to limited time and unusual circumstances, surveyors were able to cover only about 75% of this area. Nevertheless, the data gathered covering about 880 real estate parcels still provides a substantial picture of the historic housing in the neighborhood.

Workers Housing

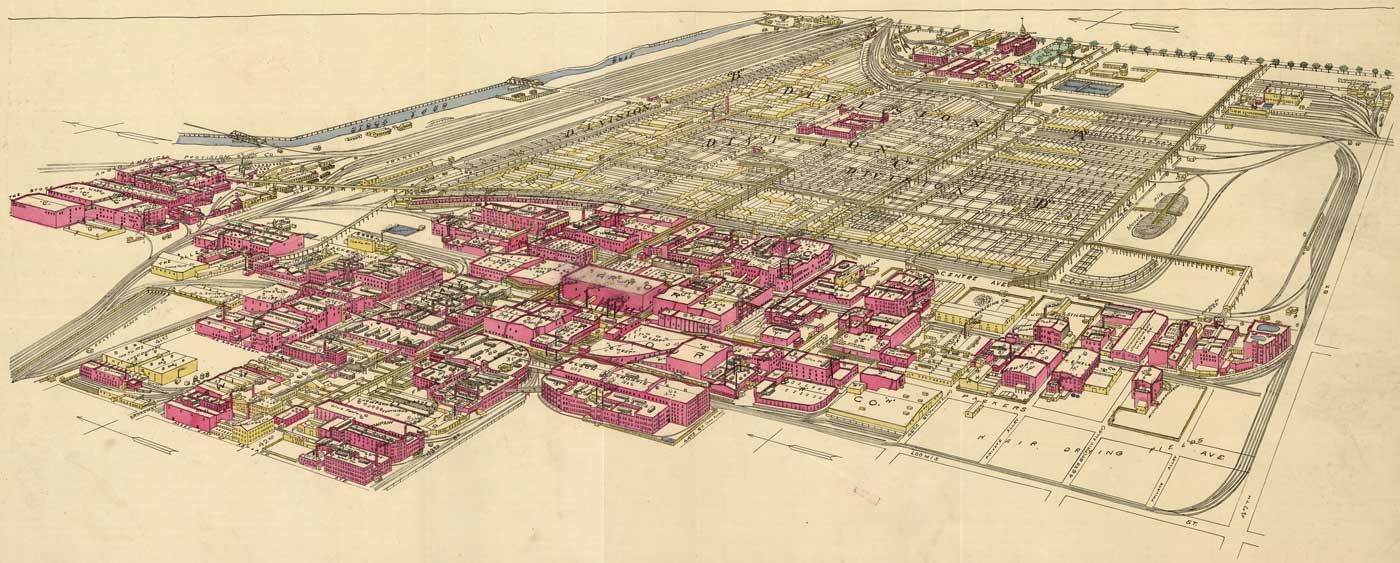

The Back of The Yards neighborhood is known around the world for its relationship with the Chicago Union Stock Yards. The sprawling stock yards opened in 1865 and over the following decades developed into one of Chicago's largest industries. As seen in the 1889 map below which looks northeast across the yards, the tiny spire of the Stock Yards Bank in the distance marks the "front" gate and managerial side of the stock yards. In the center are the sprawl of animal pens or "Yards" in yellow. Closer to the viewer in pink is the vast complex of meat-packing and associated industries of Packingtown. The blank area in the foreground is the "back" side of the yards, developed as an area of working class housing in the late 1800s for its convenient access to Packingtown jobs. By the 1920s, the stock yards and packing houses employed as many as 40,000 workers.1

Rascher's birds eye view of the Chicago packing houses & Union Stock Yards. Charles Rascher, 1890. Library of Congress G4104.C6A3 1890 .R3 TIL.

The Back of the Yards area was initially outside of Chicago's city limits. It was isolated from other neighborhoods on the east by the stock yards, on the north by railroad yards and on the west by large brickyard quarries which later became a city dump. Between the dump and the animal waste of the Stock Yards and Packingtown, the entire neighborhood was often plagued by swarms of flies which covered every surface, forcing residents to keep windows closed at all times no matter the outdoor temperature. A row of workers cottages on Wolcott Ave directly overlooked the dump piles picked over by scavengers.2

"Housing Conditions in Chicago, III: Back of The Yards," Sophonisba Breckenridge and Edith Abbott, Journal of Sociology, January 1911.

Even after annexation by the city in 1889, the neighborhood remained a slum with limited city services and poorly-maintained streets, surrounded by industries and industrial pollution. Social reformer Mary McDowell, who ran a settlement house in the area, advocated for parks and improved city services in the early 1900s. In the 1930s-1940s, the Back of the Yards Neighborhood Council organized residents to gain more improvements and recognition for the neighborhood as a connected part of the city.

Housing Types

Surveyors in our survey recorded roughly 700 buildings in portion of the survey area north of 47th Street they were able to complete. Of these buildings, 110 or about 15% were workers cottages.

The most common building type found in the survey area were larger gable-front two- or three-flats, with 279 examples (39%). These buildings feature a gable roof facing the street similar to a workers cottage but are built with two or more full-sized floors. Most often, each floor features a separate apartment with a similar floor layout. One or two entry doors facing the street lead to an interior staircase to the upper floor.

Surveyors also recorded 51 (7%) mixed-use buildings similar to gable-roof two-flats but with a ground-level first floor to accomodate a storefront business. Many of the storefronts have since been closed off and converted to rental apartments. Some of these conversions are easy to observe from the outside, while others are difficult to identify. If the building fronts directly on the sidewalk line and the door is at ground level or up a step, does that always mean that it was originally built as a storefront? Or were some buildings simply built with a first-floor unit at ground level? A definitive answer might require detailed historical research for each of the 51 buildings.

Mixed-use storefronts converted to rental apartments

The mixed-use building in the left photo at 4301 S Wolcott was built in 1907 by William Piasecki as a saloon and operated as a tavern for decades. The building in the right photo, at 4535 S Honore, was built in 1910 by Lithuanian immigrant George Lesinskas, who worked at Armour & Co. but also ran a grocery store and tavern at different times in the first floor storefront space. Lesinskas was one of the founders of Holy Cross Catholic Church and lived to be 108.

Many of these mixed-use buildings are located in the middle of side-street blocks and not just at street corners or on commercial strips. Their large proportion in the area suggests an entrepreneurial culture of home-based small businesses in the early 1900s when these structures were built. In addition to rental income from a second unit, homeowners might run a retail business or saloon out of the first floor while living in a small apartment behind.

A number of the two-flats and mixed-use buildings found in the area are larger frame buildings stretching from the sidewalk to the alley. These long buildings contain more than one apartment per floor and may have several entry doors to separate units along the long side of the building.

Frame tenement building in Back of the Yards

These large buildings are frame tenements built as cheaper housing in the late 1800s or early 1900s. The social scientists Sophonisba Breckenridge and Edith Abbott studied housing conditions in Back of The Yards and other working-class neighborhoods in 1911. Their survey records that about 10% of the houses in the neighborhood contained more than four apartments, most likely describing buildings similar to the one pictured above.3

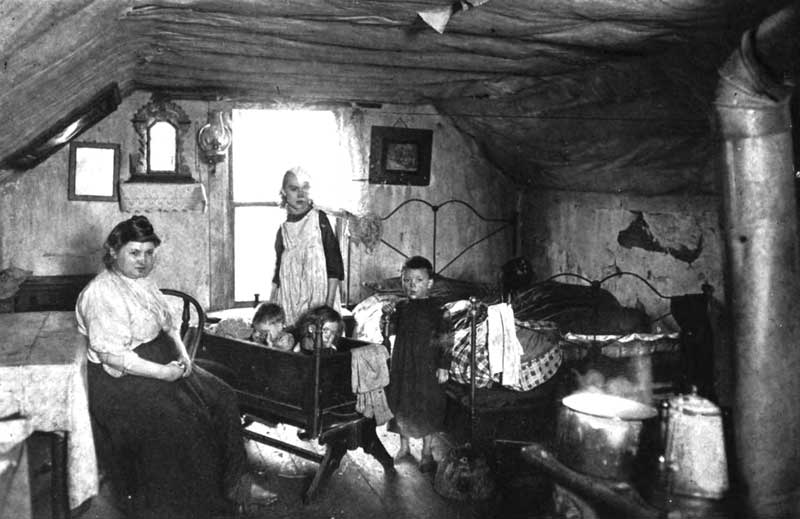

Conditions in tenement buildings as well as smaller two-flats and cottages in Back of The Yards were often overcrowded. Families commonly shared rooms with boarders or extended family. More income resources from a larger number of working adults might tide the household over during periods of unemployment. The majority of apartments in the neighborhood had four rooms, though they might be small and poorly ventilated. Only 1% were as small as the one-room apartment in an upstairs dormer of a tenement building illustrated in Breckenridge & Abbott's report:

A one-room apartment occupied by the owner and his family in a house containing four other apartments. "Housing Conditions in Chicago, III: Back of The Yards," Sophonisba Breckenridge and Edith Abbott, Journal of Sociology, January 1911.

Back of The Yards Cottages

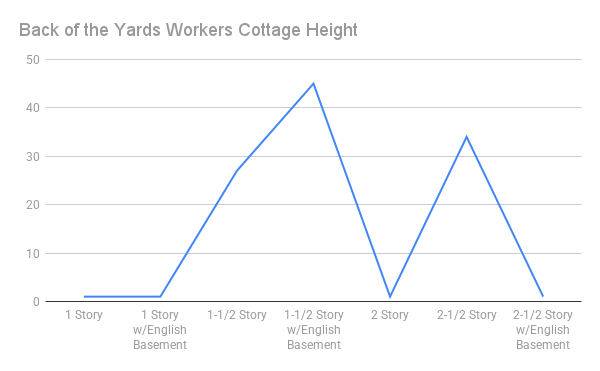

Surveyors recorded workers cottages in Back of the Yards in a wide variety of sizes. Only a few houses were 1-story cottages, with a low-pitched roof and an attic level that is too low for a usable room. More common were 1-1/2 story cottages, with a small but usable attic level. Most cottages are raised above ground level up a small flight of steps.

Examples of 1-story and 1.5-story workers cottages in Back of the Yards

Surveyors found many cottages with a second apartment unit in the lower level. These houses may have been raised in the early 1900s to build a basement or first floor underneath after sewer improvements reduced the risk of flooding in the area. Houses in the survey ranged gradually in height from cottages with a below-grade basement to those with an "English basement" half below ground to those with a first level at-grade. Beyond this height, the building was classified as a gable-front two-flat.

Range of 1.5-story to 2-story workers cottages in Back of the Yards

The cottages range across a variety of heights, with the 1-1/2 story with an English basement as the most common size. These basement levels are often lower-level apartments. Between these 45 cottages and the 35 taller 2-1/2 story cottages, over 70% of the cottages in the survey are multi-unit housing, showing the high density of housing in the survey area.

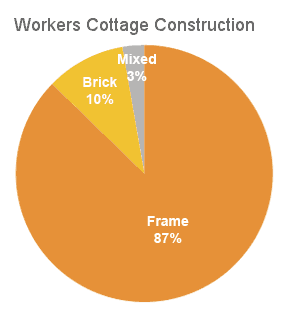

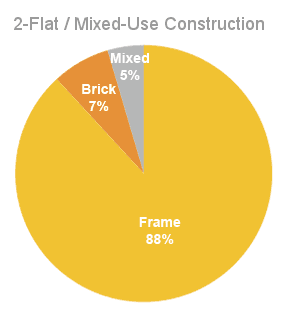

Most of the cottages in Back of the Yards are built of wood frame construction, with only 10% built of brick masonry. This proportion is nearly the opposite of the types of cottages in nearby McKinley Park just to the north. When the Back of the Yards was first developed, it was outside the city limits and outside the fire limit which mandated brick construction for better fire safety. After the area was annexed to the city in 1889 wood construction continued. The construction materials used in two-flats and mixed-use buildings is a similar proportion.

Construction dates recorded in county databases for workers cottages are not always accurate, but can show a rough idea of when the current cottages in Back of the Yards were built. Many dates are likely rounded to the nearest five years. Despite these limitations, it appears that the greatest number of cottages in the area were built around 1900. A dip in the number built in the 1890s might suggest how the 1893 depression affected house construction in the neighborhood.

Construction dates of two-flats and mixed-use buildings appear to be slightly later, peaking in the years around 1900. This may indicate a higher demand for denser housing than in the decade earlier when the first workers cottages were built.

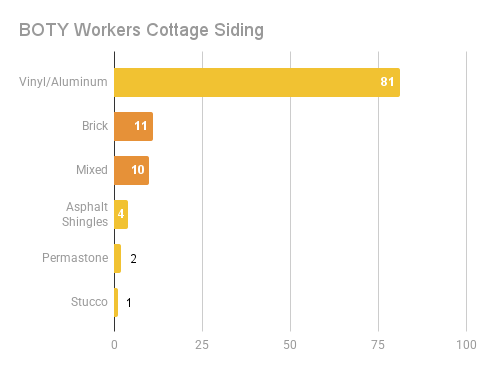

Because most workers cottages in Back of The Yards are made of wood, their age may not be apparent. Like wood-frame houses in Logan Square and South Chicago, they are most commonly covered in vinyl or aluminum siding. Often the siding covers earlier layers of asphalt shingles over the original wood clapboard.

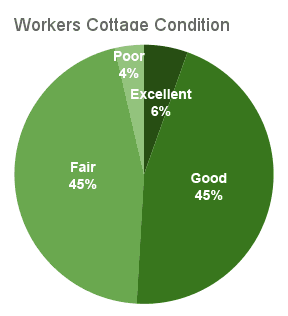

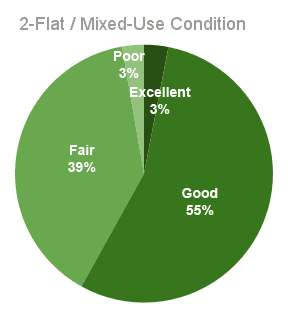

Surveyors rated the apparent condition of the houses in the area. Only about half were considered to be in good or excellent repair. The large number of houses rated as "fair" condition, meaning there were visible signs of deferred maintenance, shows the need for support for housing repair funding in this area. A small number of houses were listed in poor condition, houses which might be damaged or in urgent need of repair. Two-flats in the survey were rated slightly better in condition.

Overall, most cottages and two-flats in Back of the Yards were built as functional, no-frills working class housing. Most are nowadays hidden behind functional, no-frills vinyl siding. They may have been originally built cheaply or well, and have years of low-budget maintenance, but at over 120 years old these houses continue to be an important resource as affordable housing in Chicago.

The Working Man's Reward

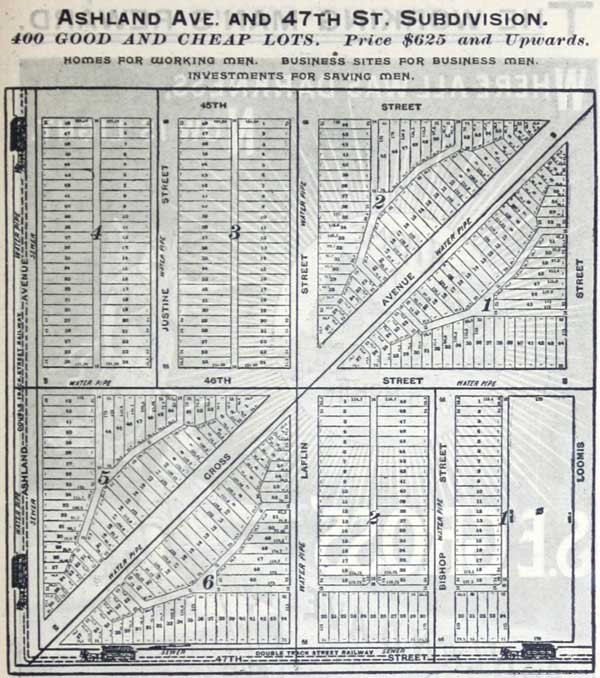

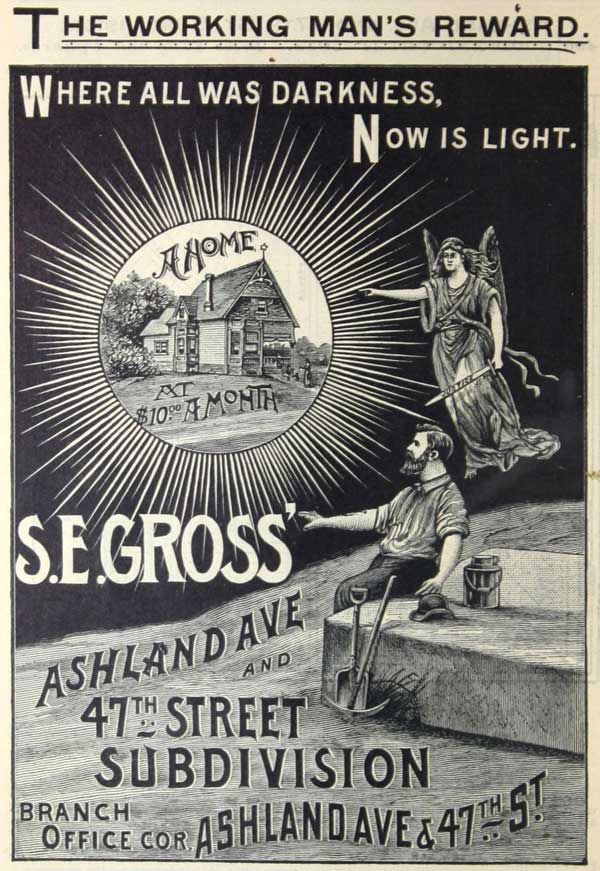

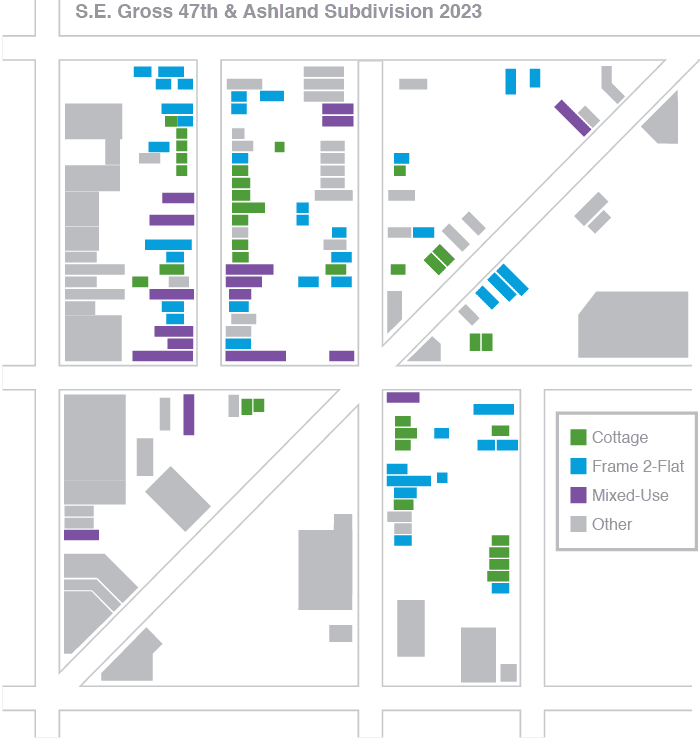

In 1887, developer Samuel E. Gross purchased 40 acres of land at the heart of what would become the Back of the Yards neighborhood. He subdivided the land into eight blocks with a diagonal street leading from the intersection of horse-car transit lines at 47th & Ashland toward the meatpacking plants of Packingtown where residents might work. As he had done in previous housing developments, he named one of the streets after himself. In this case Gross Avenue was unintentionally fitting, because the street lead pedestrians toward one of the main gates to Packingtown: the source of filth, flies, manure dust and all manner of foul smells overshadowing the neighborhood!

Tenth Annual Illustrated Catalogue of S.E. Gross' Famous City Subdivisions and Suburban Towns, S.E. Gross, 1891. Internet Archive

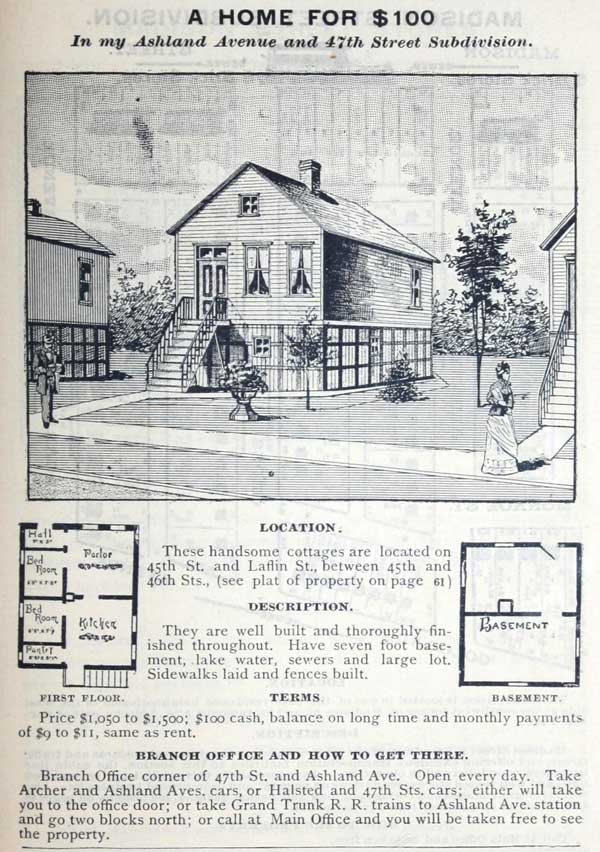

Gross achieved great success as a citywide developer in the 1880s-1890s by building simple workers cottages from a limited number of plans, offered on affordable payment terms directly from the builder, as well as selling empty lots for buyers to build their own houses. An advertising pamphlet from 1891 illustrates one of the fourteen spec houses Gross built in a row in his Back of the Yards development. The frame cottage measures about 20' wide by 25' deep with four rooms for the price of $1,050 to $1,500 or $9 to $11 per month with a $100 down-payment. Perhaps due to flooding issues in the neighborhood, the unfinished basement level looks only slightly excavated below ground level and is not accessible from the first floor. The advertisement claims that the street has access to water and sewer lines, though the floor plan shows no indoor bathroom connected to such services. To save construction costs, the buyer was responsible for adding these amenities themselves.4

Tenth Annual Illustrated Catalogue of S.E. Gross' Famous City Subdivisions and Suburban Towns, S.E. Gross, 1891. Internet Archive

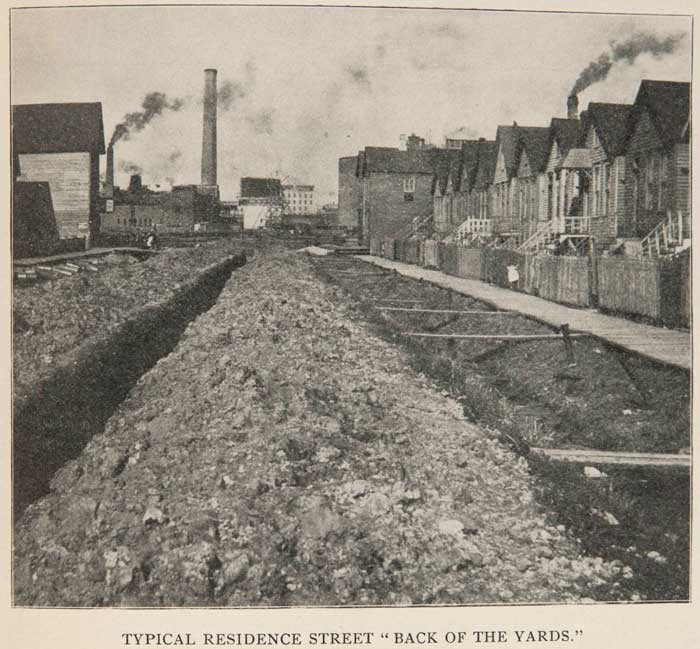

A 1901 photo below shows the reality of the Gross cottages on the east side of the 4500 block of Laflin St. Instead of house in a wide yard with young trees, these cottages sat shoulder to shoulder on typical city lots with only a tiny green space in front behind a picket fence. In front of the sidewalk is a ditch where residents have laid planks to cross on a little bridge. The row of cottages would be about 13 years old in the photo and perhaps in need a bit of paint and some repairs to the front stair railings.

Image from "Some Social Aspects of the Chicago Stock Yards," Charles J. Bushnell, American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 7, No. 3 (Nov., 1901)

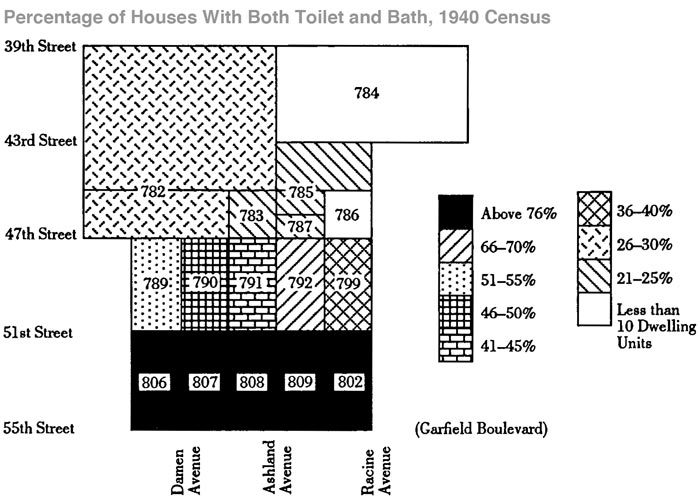

Laflin Street appears to be torn to rubble, perhaps in the midst of a project to install a sewer or water main laying on the surface. A dozen years after the houses were built, homeowners finally were able to connect to city water and sewer services. Investing in the plumbing for an indoor bathroom may still have been still out of reach of the poorest homeowners in the area. Decades later, the 1940 census records that fewer than 25% of the houses in the Gross subdivision (Census tracts 785-786-787 below) had both an indoor toilet and bathtub. Owners of the cottages and landlords of the two-flats in this area were unable to make this investment in their properties.

Chart reproduced from Pride in the Jungle: Community and Everyday Life in Back of the Yards Chicago, Thomas J. Jablonsky, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993.

In Upton Sinclair's 1906 novel The Jungle, the Rudkus family proudly purchases a four-room cottage similar to the Gross cottages for $1,500 with monthly payments of $12. The book desribes the house as two miles south of Packingtown, which would place it close to 59th St in West Englewood, not Back of the Yards. Living farther away from the Stock Yards and industrial pollution may have been a step up from the poor conditions of Back of the Yards streets, but it was also a long inconvenient walk to work in Packingtown. The most unfortunate circumstance for the Rudkus family, however, is that the home was purchased from a predatory contract seller. Their monthly house payments go to pay off the interest on the loan, not the house itself. When the family misses a payment due to unemployment, the seller repossesses the cottage and the family is left with nothing after more than three years of investment.5

Though the fictional family's experience is likely based on local stories that Sinclair heard while researching the novel, buyers in Samuel Gross' subdivision likely received fairer terms. Across the city, many cottage owners felt that Gross was on the side of the working class. His financing allowed working families access to homeownership that they might not have been able to achieve previously. In 1889, the Workingmen's Party tried to draft Gross as its mayoral candidate, though he declined the offer.6

Another page in the 1891 advertising booklet provides one of the most striking images in early Chicago real estate. A working man puts down his pick and shovel for a lunch break from the pail sitting next to him. In his moment of rest, an angel of justice appears from the darkness to show him a vision of what is the purpose of his labor: a home at $10 a month! The text directs the reader to 47th & Ashland subdivision, though the home pictured is far more elaborate than the simple cottages Gross offered for sale there.

Tenth Annual Illustrated Catalogue of S.E. Gross' Famous City Subdivisions and Suburban Towns, S.E. Gross, 1891. Internet Archive

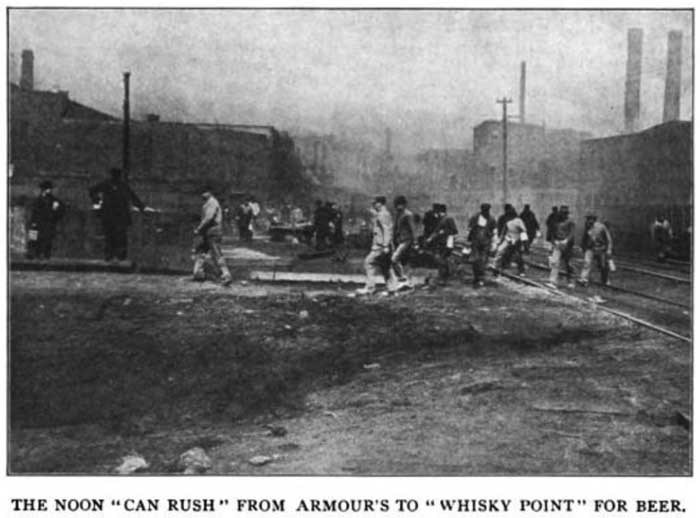

Part of the appeal of buying in Gross' 47th & Ashland subdivision was that a worker didn't just have to dream of his home while eating lunch from a can on a stone in a featureless industrial wasteland, he could just walk a few blocks and have a hot meal at his actual house. He might even avoid the alcoholic temptations of the free salty buffets at Whiskey Point to have a wholesome meal by a short walk to his own home.

Image from "Some Social Aspects of the Chicago Stock Yards," Charles J. Bushnell, American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 7, No. 3 (Nov., 1901)

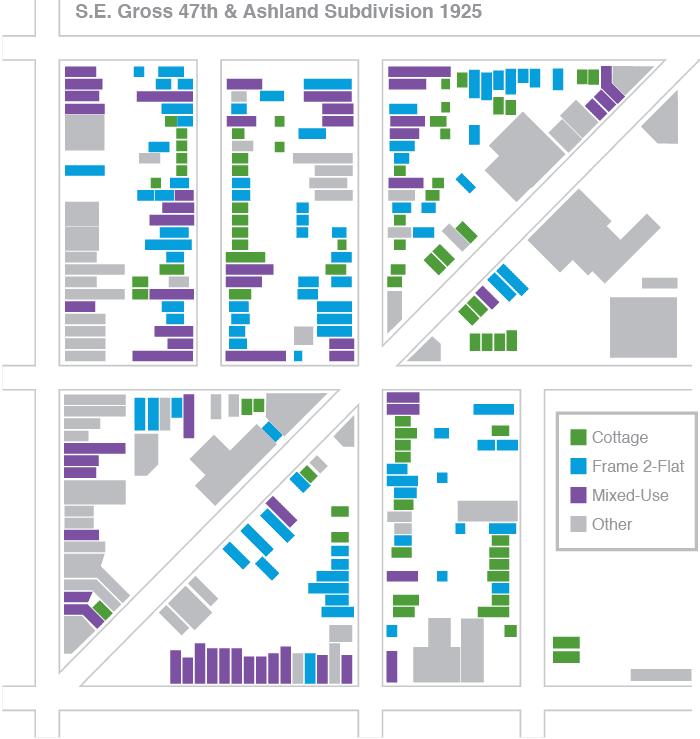

Despite the stirring imagery of his advertising, houses in Gross' 47th & Ashland development seem to have been slow to sell. Fire insurance maps from 1895, seven years after the area was subdivided, show several groups of completed cottages and wood-frame two flats beyond Gross' original row of fourteen spec houses, but there are also many undeveloped parcels, as shown below. Matching the size and building materials shown on the fire insurance maps to the categories used in our field survey may be a little inexact, but the general pattern of development of the blocks is visible. Near the center at the top is the line of fourteen cottages first built by Gross in 1888. Other clusters of cottages may have been built by Gross as well, or by other builders or homeowners who bought empty lots in the subdivision.

By 1925, the blocks were far more densely developed. In the years between the two maps, employment in Packingtown increased from roughly 25,000 to 40,000, no doubt increasing demand for housing. As early as 1911, Sophonisba Breckinridge and Edith Abbott noted: "Small frame cottages have gradually been displaced or outnumbered by tenements built for two or more families." By 1925 the original row of Gross cottages had been largely replaced by larger frame two-flat housing. Some of the small old cottages were moved to the back of the lot, others were likely expanded to become taller two-flat buildings. Two-story mixed-use buildings with storefront retail proliferated even on side streets.7

In 1937 the diagonal Gross Ave was renamed McDowell Ave in honor of Mary McDowell, head of the settlement house on the street who had advocated for improved conditions and services in the neighborhood.

Production in the meatpacking plants peaked around 1920. Many closed by the 1950s and the Union Stock Yards itself closed in 1971 to become an industrial park. Over these decades Back of the Yards has gradually lost population and lost many of its old houses. The 4500 block of Justine Ave retains its original density, with several groups of intact workers cottages in 2023.

Of the original row of fourteen Gross workers cottages on Laflin Street, only two isolated houses remain. One in fact looks largely unchanged from its original condition. The lower level has been rebuilt in brick, modern siding and a porch added, but with a grassy side yard where a neighboring cottage once stood it doesn't look so different from that idealized illustration from 1891!

Streetview image of 4521 S Laflin

References

1 Pride in the Jungle: Community and Everyday Life in Back of the Yards Chicago, Thomas J. Jablonsky, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993.

2 The Working Man's Reward: Chicago's Early Suburbs and the Roots of American Sprawl, Elaine Lewinnek, Oxford University Press, 2014, p 67.

3 "Housing Conditions in Chicago, III: Back of The Yards," Sophonisba Breckenridge and Edith Abbott, Journal of Sociology, January 1911.

4 Tenth Annual Illustrated Catalogue of S.E. Gross' Famous City Subdivisions and Suburban Towns, S.E. Gross, 1891.

5 The Jungle, Upton Sinclair, Modern Library Paperback, 2006.

6 City of American Dreams: A History of Home Ownership and Housing Reform in Chicago, 1871-1919, Margaret Garb, University of Chicago Press, 2005.

7 "Housing Conditions in Chicago, III: Back of The Yards," Sophonisba Breckenridge and Edith Abbott, Journal of Sociology, January 1911.