Historic postcard circa 1908, courtesy Logan Square Preservation

A History of the Chicago Workers Cottage

The workers cottage house type derives from earlier vernacular house styles in the Midwest. These simple gable-roofed dwellings were typically built with a central entrance on a side perpendicular to the roof orientation. In Chicago, this house style was adapted to fit the constrained urban space of a typical 25' x 125' Chicago city lot by turning the building and entry to face the street.

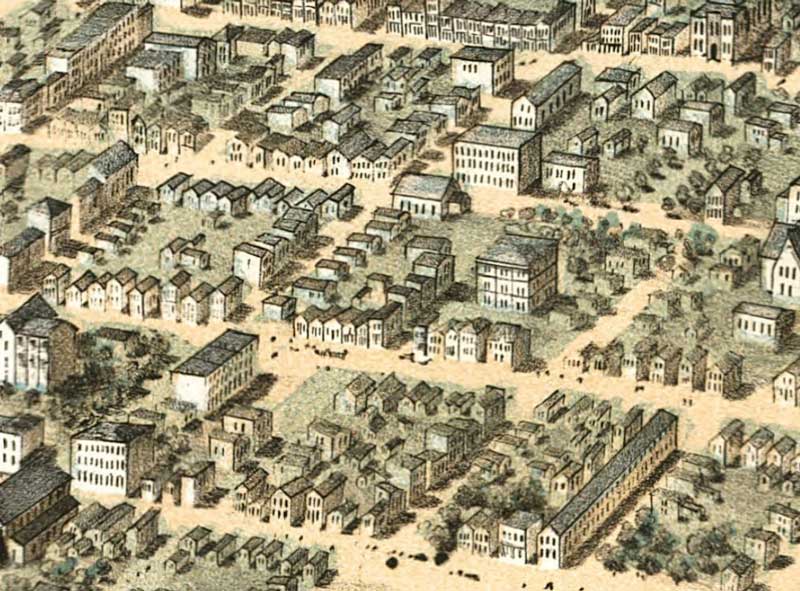

A birds-eye-view map from 1868 shows hundreds of these simple gable-roofed frame houses crowding the streets on the north, south and southwest outskirts of the central business district. Though the outer areas of the map are not depicted in great detail, zooming in to the area of what is now Chicago & Wabash Avenues we can see several rows of 1½ and 2½ story frame houses interspersed among larger brick tenement apartments. Three years later all of the houses in this area would be destroyed in the Great Chicago Fire.

Detail of Chicago in 1868 from Schiller Street north side to 12th Street south side, Chicago Lithographing Co. 1868, Library of Congress G4104.C6A35 1868 .R8

After the 1871 fire and a smaller conflagration in 1874, Chicago banned construction of new wooden buildings within the city limits, despite the protests of working-class residents who could not easily afford expensive brick construction. Buyers seeking more affordability sprawled to Lake, Jefferson and Lakeview townships outside city limits to build frame houses without restriction. Industries such as the Chicago Stockyards, too, moved to the city outskirts, increasing demand for new subdivisions and working-class housing. Many of these outlying areas were later annexed to the city and received city water and sewer services.

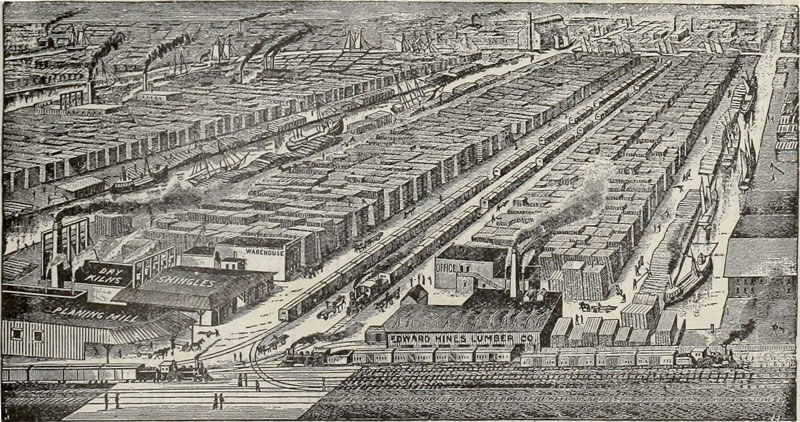

The rapid development of these new neighborhoods was enabled by Chicago's location as a central marketplace of natural resources from a wide territory. From northern Wisconsin and Michigan, dense old-growth pine forests supplied the lumberyards stretching southwest of downtown Chicago along the South Branch of the Chicago River. The world's busiest lumber market supplied the growing sprawl of workers housing around Chicago and also shipped materials by rail to build the new towns of the Midwest and West. The "balloon frame" technique of house building, which used long, straight upright beams to quickly frame walls of the house, was more economical than older methods to construct and made possible by standardized sizing of boards from the centralized lumberyards.

Earl Hines Lumber Yard on the Chicago River, from The Canada Lumberman magazine, January 1903

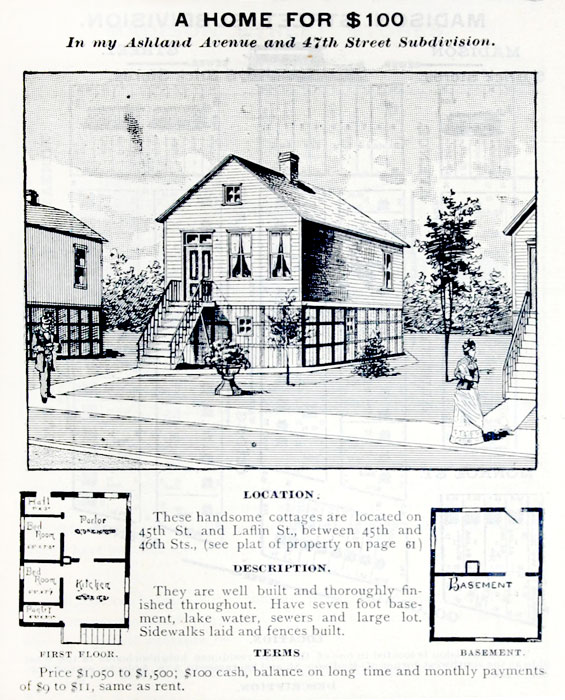

During the building boom of the 1880s-early 1890s, the city sprawled outwards along new commuter railroad and horse-car transit lines. Commercial developers and real-estate speculators purchased former prairie and farmland to build new subdivision housing, including thousands of new workers cottages. Samuel E. Gross ran one of the larger development firms and may be best known today in part becuase of the well-illustrated advertisements his company published. Large builders often offered payment in four annual installments which made the houses affordable to working-class families. Cottages were also built by independent carpenters and sometimes homeowners themselves.

Back of the Yards workers cottage illustrated in Tenth Annual Illustrated Catalogue of S.E. Gross' Famous City Subdivisions and Suburban Towns, 1891

Upton Sinclair's 1906 novel The Jungle describes the Rudkus family's struggle to keep up with the monthly payments on a house in the same area as the one illustrated in Gross's brochure above and perhaps similar to it. While many families no doubt were taken advantage of by unscrupulous developers, successful home-ownership meant a hard-won bit of stability at a time when working class jobs provided little economic security. In tough times the family could rent extra rooms or take in boarders to help pay off the mortgage. In prosperous times they could add room for a growing family with an addition in back, or even raise the entire house to build another rental apartment floor underneath. Some frame two-flat and three-flat buildings started out as smaller 1-story workers cottages. Workers cottages were often altered extensively over the years. These modifications tell the unwritten history of all the families who have called these places home.

House Histories of Individual Workers Cottages

Have you found an interesting story about the history of your workers cottage? Please share with us!