4913 S. Wabash Ave

Mother and Son

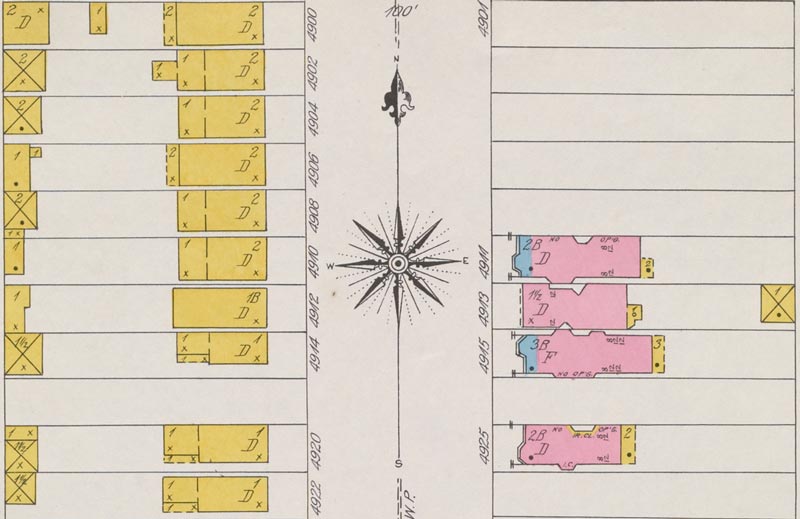

The brick workers cottage at 4913 S. Wabash with ornate arched decorations above the windows in Chicago's Grand Boulevard neighborhood has a unique history. Elizabeth Elcock and her son Edward Elcock Jr. bought the property jointly in March 1893 and had the brick cottage built soon thereafter. Unlike most cottages in Chicago, the house extends nearly the full width of the 25-foot property without space for a gangway alongside. When neighbors built a brick three-flat next-door to the south in 1894 and a two-flat to the north the year after that, the new cottage might have seemed boxed-in. Across Wabash Ave the cottage faced a row of wood two-flats and cottages that were built in the late 1880s a few years earlier.

Detail of 1895 Sanborn Insurance Map of 4900 block of S. Wabash Ave. Map Library at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

The Elcock family had come to Chicago from Belfast, in what is now Northern Ireland, in 1867 when their son Edward Jr. was eight years old. As a young man Edward worked as a skilled machinist or engineer, like his father. In 1887 Edward Jr. moved to 4912 S. Michigan, the lot directly behind the cottage on Wabash. He had just eloped with a young woman named Matilda Gottfried against the wishes of her father Mathias Gottfried, who was owner of one of the largest breweries in Chicago. Despite the rocky start of the marriage, Edward was eventually accepted by his father-in-law. His relationship with his own father was a different story. In 1881 a family argument escalated to the point where Edward Sr. attacked his son with a sledge hammer and a broken bottle, destroyed the family piano, and threatened to shoot his son Edward and wife Elizabeth with a revolver. His violent behavior and alcoholism may have been due to chronic pain from an industrial work accident which had crushed his hand several years earlier. Edward's parents divorced soon after the assault and his father lived on his own in a series of boarding hotels.

Around this time Edward Elcock and his business partner Joseph R.Hansell founded the Hansell, Elcock Co. iron works at 23rd & Archer, which created cast-iron and steel beams and girders for bridges and factory buildings.

Hansell, Elcock Co. 1892 catalog advertisement. Ryerson and Burnham Art and Architecture Archives.

Mother Elizabeth and her grown daughter (also named Elizabeth Elcock) lived together in the new cottage on Wabash. Brother Edward and his wife Matilda had no children and lived in the house directly to the east on Michigan Ave. Sister Caroline and her husband Andrew Hoffman lived a half-block south at 5006 S. Michigan with their three daughters. Perhaps Edward and Matilda's house was the central place where the family met together, and the backyard behind the cottage at 4913 was a pathway across the alley to the house on Michigan.

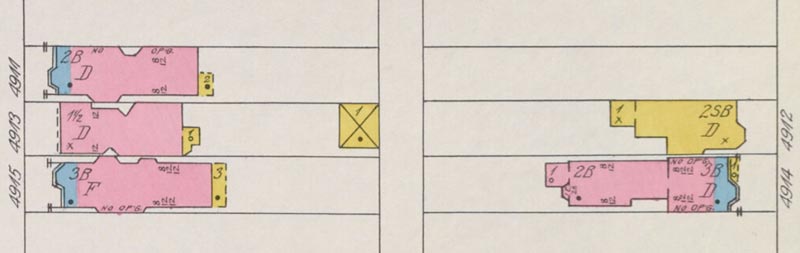

Detail of 1895 Sanborn Insurance Map of 4900 block of S. Wabash & Michigan Aves. Map Library at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Daughter Elizabeth passed away in 1900 at the age of 38. Several years later, Edward rose to become president of the Hansell-Elcock Iron Works, and with this new prosperity he and Matilda moved to a greystone mansion at 4806 S. King Dr. in 1907. Mother Elizabeth lived alone at the little cottage until she passed away in 1916 at 80 years old.

The Bombings

In the late 1910s, tens of thousands of African-Americans moved to Chicago from southern states in search of better job opportunities and freedom from Jim Crow oppression. From 1917 to 1920, Chicago's African-American population grew from 44,000 to 109,000. Many newcomers settled near family in early African-American neighborhoods on the West Side and South Side. Families who wished to live outside these areas were sometimes met with violence by white residents. From 1917-1921, 58 bombs were placed at the homes of African-Americans who had recently moved Into homes that had previously been owned by whites, or at the homes of real estate agents who helped African-Americans find housing. Numerous bombs were placed a few blocks east of Wabash, but one targeted a house on the same block as the cottage. During this time, white real estate agents and the Kenwood and Hyde Park Property Owners Association openly promoted racist animosity against African-Americans. Under the cover of night, white terrorists threw homemade dynamite bombs from automobiles or placed them in the entryways of buildings. Anonymous letters often preceded the bombings to intimidate new homebuyers. Two people were killed and scores injured from these years of terror, but police investigators turned up few clues. Only two bombing suspects were ever arrested and both were released for lack of evidence.

Detail of 1922 map "Houses Bombed in Race Conflicts Over Housing July 1, 1917 - March 1, 1921". Location of cottage at 4913 S. Wabash added in red.

Despite the intolerance of some neighbors, Grand Boulevard had been a mixed-race neighborhood for several decades. Across the street from the cottage at 4913, the African-American Price family had lived in the workers cottage at 4912 S. Wabash since 1890. The mixed-race actress Ivy Hubbard bought the three-flat at 4915 next-door to the cottage in 1914. Within the next few years the block shifted from majority white to majority Black residents. By the 1920 census, most of the residents of the street were Black families recently arrived from Kentucky, North Carolina, Tennessee and other states. In contrast to the decade earlier, many of the new residents did not own their homes but rented them. Only a limited number of banks and building associations made loans to African-Americans, making it challenging for many to afford buying property even in Bronzeville.

Giles McClendon purchased the cottage at 4913 from Elizabeth Elcock's granddaughter in April 1918. He was 73 years old, a successful African-American farmer from the town of Dublin, Georgia. He had been born in the time of slavery and lived through the Civil War as a teenager. He married and raised a family near Dublin in the 1870s, all the while saving money to buy land. By 1890 he owned 577 free and clear acres of his own farmland. He became involved in local Republican party politics and was respected enough in the party to serve as an alternate delegate for the 1896 Republican National Convention in St. Louis which nominated William McKinley for president.

Giles McClendon somewhere in the crowd at 1896 Republican National Convention, St. Louis.

Its unclear from limited records if there was a specific reason which prompted Giles McClendon to come to Chicago and buy a cottage. Did he come north to be closer to family members? He was older than most of the African-Americans who came to Chicago during the Great Migration in search of better jobs and more freedom. But after buying the house in 1918 he did not immediately move to Chicago. In the 1920 census, he was still living on his farm near Dublin, Georgia, while the cottage at 4913 was rented out to another family.

The Rental House

Robert and Fannie Lawler rented the cottage for a few years until about 1921. Though they did not live here long, the 1920 census provides a snapshot of their time here. Robert worked as a bag handler at a laundry. 36-year-old son John worked as a porter and 32-year-old daughter Katie worked as a maid. Their youngest son Albert and his wife May lived a few blocks away in a rented room. The family had recently moved to Chicago from Springfield, Illinois.

Fannie & Robert Lawler at the wedding of Fannie's nephew, William Henry Murrell and Sarah Francis Robinson in 1893. Courtesy Deborah Hanes.

Across the street from the cottage and a few doors south, a small industrial building was built on the empty lot at 4918 in 1914. At the time of the 1920 census, the Kraus Bros Loewy Co. ran a commercial laundry here. This may have been the laundry where Robert Lawler worked. Before 1923, Chicago did not have comprehensive zoning laws which could restrict small manufacturing industries from locating in the midst of residential areas. The business right next to houses may have provided jobs for the neighbors on Wabash but probably also added noise, traffic and air pollution to what had previously been a quiet residential street. Though the factory was built a year or two before the block shifted to majority Black residents, the presence of an industrial building directly next to houses follows a too-common pattern of environmental racism of elevated pollution in minority neighborhoods.

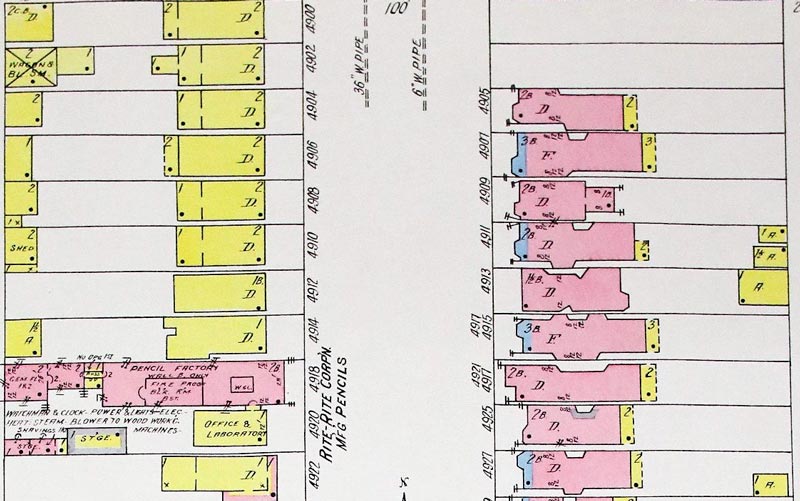

Detail of 1925 Sanborn Fire Insurance map of 4900 block of S. Wabash Ave.

In 1922, businessman Hyman E. Golber bought the industrial laundry building at 4918 and next-door house at 4920 for use as a factory and office for a new business manufacturing mechanical pencils. The Rite-Rite Corporation eventually outgrew the small buildings, moved its offices downtown and in 1941 built a factory in Downers Grove employing 150 people. The company was later acquired by Dixon Ticonderoga and the pencil rebranded as the Dixon Rite-Rite pencil.

Detail of Rite-Rite Corporation ad, Feb 1, 1925 Chicago Tribune

The Lawlers were living in the cottage at 4913 during the "Red Summer" of 1919. On July 27, unrest began after an African-American swimmer at 29th St beach was killed by white bathers throwing stones. Black witnesses protested when police failed to arrest the stone-throwers. Over the next week, violence raged across several neighborhoods. 38 people were killed, more than 500 injured, and a thousand African-American families left homeless by arson. White gangs of teenagers and young men were responsible for much of the violence. Athletic clubs from the neighborhoods west of Bronzeville such as "Ragen's Colts" and the "Hamburgs" (which included the future mayor Richard J. Daley) attacked Black homes and anyone they found on the street. From their window, the Lawler family may have been able to see the fires set by mobs a few blocks away near 47th and Wells on the night of July 29th. Earlier that same day, police had shot and killed 19-year-old Thomas Joshua a block south of the cottage. After midnight that night, police shot 40-year-old Ira Henry in the alley a block west of the cottage. Officers claimed to have seen both men threatening them with guns. The Lawlers had lived a few miles away from the mayhem of the 1908 race riot in Springfield, but the violence in Chicago was happening right outside their door.

The Lawler family moved to a different rental apartment nearby in 1921. At some point after that, Giles McClendon finally moved north from Georgia to live in his cottage. In the 1930 census, he is listed as a widower living here along with an adopted daughter Bernice who was 19 years old. She was the daughter of a woman whom Giles and his wife Laura had taken in to their home as a young single mother decades before. Perhaps Bernice thought of 85-year old Giles as her adopted grandfather. Sadly, Bernice passed away in 1931 at only 20 years old. Giles continued living at the cottage alone until his death in 1937.

A New School

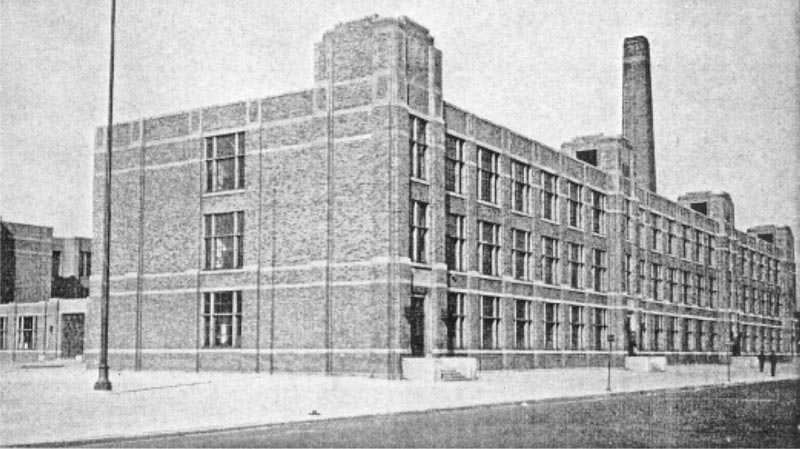

By the late 1920s, the Grand Boulevard and Bronzeville neighborhoods were crowded with families and children. To alleviate overcrowding at Wendell Phillips High School on Pershing Rd, the Chicago Board of Education chose the block of Wabash Ave across from the cottage as the site for a new high school. The modern building was designed by school architect Paul Gerhardt to accommodate more than 2600 students. In 1927 the city paid the homeowners on the west side of Wabash roughly $5,000 to $7,500 for their houses and cleared the block. Construction of the school started in 1931 but stalled the next year due to budget difficulties during the Depression. For two years Giles McClendon would have looked out from his window at 4913 to see only a bare concrete foundation with skeletal girders. Finally in 1934 construction resumed with Federal assistance and the grand brick building nearly the length of a city block was completed in 1935. The school was at first called "New" Wendell Phillips but a year later was renamed Jean Baptiste Point Du Sable High School after Chicago's first non-native settler and first African-American resident.

Du Sable High School shortly after completion in 1935. Du Sable High School Landmarks Designation Report, 2012.

Many Du Sable graduates went on to later fame. Timuel Black graduated here in 1937, Harold Washington in 1939. DuSable Museum founder Margaret Burroughs taught art here for 22 years. Music teacher Captain Walter Dyett was a great influence on many students. Nat King Cole, Dinah Washington and Bo Diddley went to school here, along with many other talented but less-well-known musicians. Over the many years, how many of those young students sat daydreaming in class gazing out the window at the little cottage across the street?

After World War II, a second wave of the Great Migration brought more African-American families to Grand Boulevard and Bronzeville. Between the 1940s to 1960s, DuSable was crowded with over 4,000 students. The school held graduation ceremonies in winter and spring to accommodate the number of students.

After Giles McClendon passed away, the little cottage at 4913 may have been foreclosed on and owned by the Chicago Title & Trust Co. In 1946, Maude Flowers bought the cottage at 4913 from the bank. Maude was 70 years old and retired from a career as a cook in a restaurant she ran with her common-law husband Sam Ramirez. It would have been illegal for an African-American and Hispanic couple to marry at that time. It's likely that Maude did not live in the cottage but bought the house as a home for her youngest sister Anna Mae Flowers. Maude had taken care of her twenty-years younger little sister when she was a teenager, and perhaps still looked out for her many years later. In the 1950 census, Anna Mae lived in the cottage at 4913 with her four grown children Henry, Dorothy, Willie and Annie Lea, as well as Henry's wife Helen and four lodgers, including a newborn baby. The little cottage was crowded, just like the rest of Bronzeville.

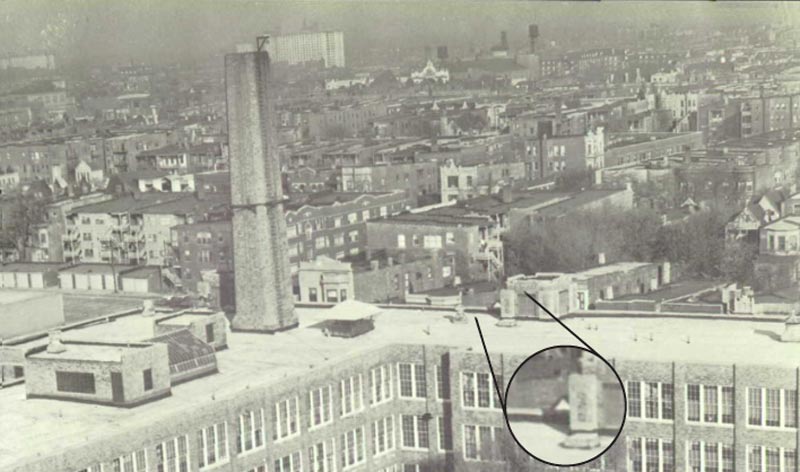

Looking northeast from newly-built Robert Taylor Homes. Detail of photo from 1962 DuSable High School Red & Black yearbook.

A photo looking over the roof of DuSable High School toward the heart of the Bronzeville neighborhood shows how uncommon workers cottages were in the area by the 1960s. The cottage at 4913 is just barely visible peeking above the roof the the school. There are a few wood frame gable-roofed houses in the photo, but most buildings are larger brick apartments and two- or three-flats. Many of these had been subdivided over the years of high housing demand into cramped kitchenette apartments with shared bathrooms, the sort evoked in Gwendolyn Brooks' 1945 poem "Kitchenette Building". In the distance at center, a low white building with a fanciful top is the Regal Theater at the heart of Bronzeville where Russell Lee took one of the neighborhood's most iconic photos.

The 1962 yearbook photo above was taken from one of the windows of the newly-completed Robert Taylor Homes, the largest public-housing project in the country, with over 4,000 units in 28 buildings stretching nearly two miles along State Street from 54th to Pershing Rd. The Chicago Housing Authority built the project to alleviate the overcrowding in Bronzeville and replace dilapidated apartments with decent modern construction. But lack of maintenance and short-sighted CHA policies quickly turned the high-rises into notorious concentrations of poverty and crime. Over the years, how many Robert Taylor teenagers who dodged gang boundaries to walk to school at DuSable looked out from the classroom windows and noticed the anachronistic little cottage across the street?

Maude Flowers passed away in 1957. The cottage at 4913 had a number of owners over next few decades. Some of them struggled with mortgage payments and the house was lost to foreclosure several times. The Clayton family owned it for six years in the early 1970s. At some point one homeowner remodelled the house with glass block windows around the front entry.

The Chicago Housing Authority moved the last of the Robert Taylor Homes residents out in 2005 and the high-rises were demolished by 2007. Without the thousands of children from the next-door housing project, DuSable High School lost enrollment and was closed in 2005. Nowadays several smaller college-prep schools use the landmarked building.

Still the house at 4913 remains amidst the many changes on Wabash Ave.

The Cottage Today

Photos by Tom Vlodek

By Matt Bergstrom

Have you found an interesting story about the history of your workers cottage? Please share with us!